Quantum computing is one of the first great technologies of the 21st century, but the details are still shrouded in mystery. I can explain conventional digital computing down to the electron in a MOSFET, and with this newsletter, I have made it my mission to do the same for quantum computing.

Welcome to the Quantum Edge newsletter. Join me in my quest to translate the mysteries of the quantum world to the language of the dinner table and the coffee shop.

Issue 14.0, November 28, 2025

In today’s newsletter: Introduction to quantum computer math - How superposition allows faster math than conventional computers

Last issue gave you a peak into number storage with qubits. This issue is going to illustrate how that can lead to much, much faster math. Really faster math. But first we need a better picture of superposition. With quantum supposition, a qubit can hold the value 0, 1 and everything in between.

How does superposition work? How can a single qubit hold more than one value? Good questions. Three of the most common ways I’ve read to describe a qubit storing data are:

A qubit in superposition is both 0 and 1 at the same time

A qubit in superposition is 0, 1 and everything in between

A qubit in superposition is both 0 and 1 with a probability value of being one or the other.

How is that possible and how does a specific answer to a math problem eventually come out of that?

Delving Into the Big Mystery

Unfortunately, while the idea of holding all combinations of an answer at once may be illogical, it is what a qubit does. It’s the big mystery for everyone. While the mechanics underlying superposition may be obscure, there are ways to visualize it. Doing so requires trying to imagine what a subatomic particle in qubit form looks like close up.

As we’ve discussed before, some elemental particles, like the electron are thought of as infinitely small points. That’s true, but it’s also an oversimplification. When trying to better understand how particles interact, some physicists think of particles as more than points. Some think of them as fields of energy, some think of them as small vibrating strings, and some as small standing waves.

How Does a Point Becomes a Wave?

Here’s a thought exercise visualization to help answer that question.

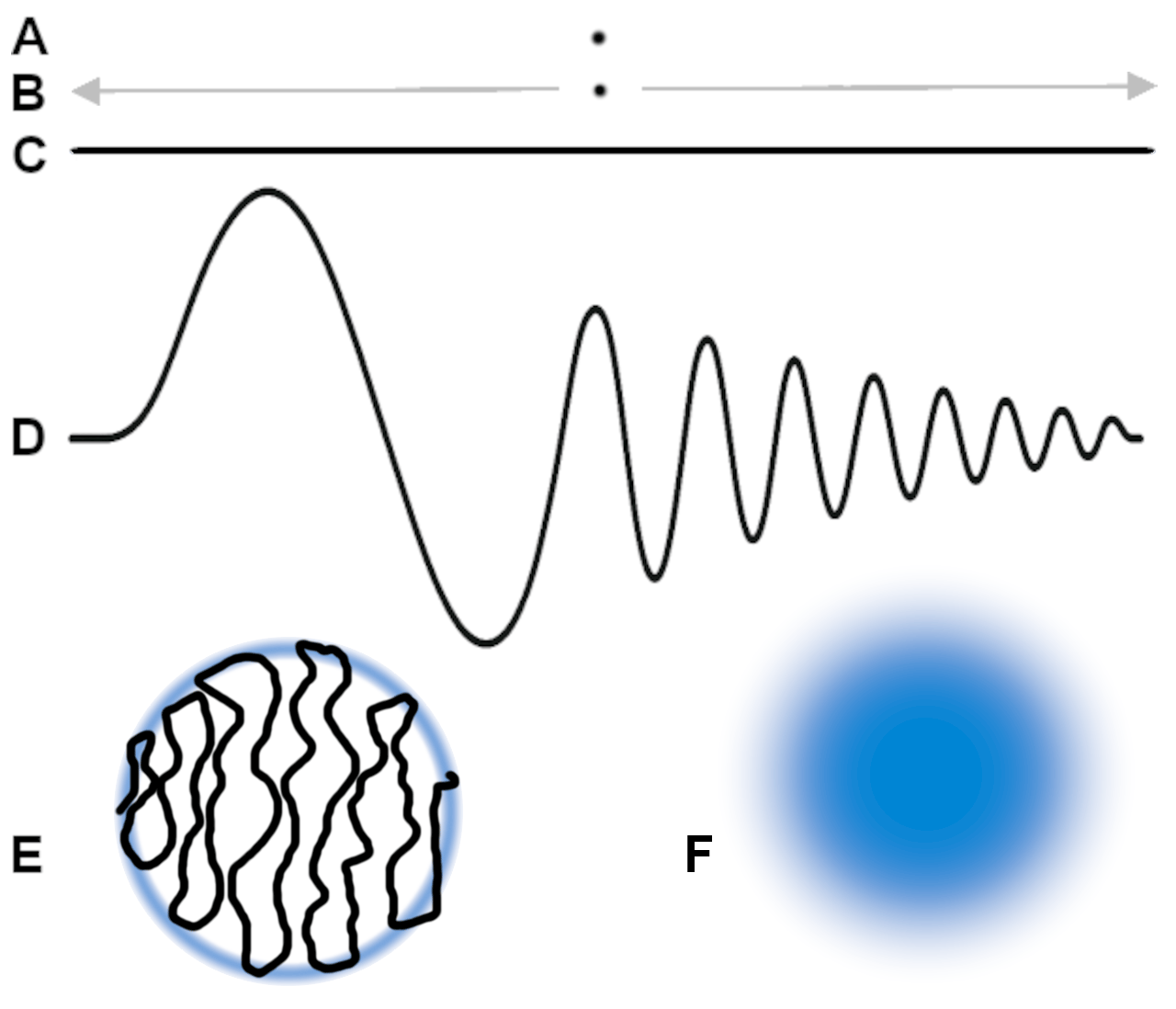

Figure 1. How a point could end up as a string or a sphere

Imagine you have a point, as in Figure 1, (A). Move that point back and forth fast enough (B) so that it looks like a line, as in (C). Now take that imaginary line, grab one end of it and shake it up and down. You will get a wave, like (D). Add some chaos into your wave shaking, and you might get a string balled up into a circle (E). That circle can influence other particles and can be visualized as a fuzzy sphere, like (F).

To get to a particle acting as a qubit to hold values, take figure 1, (D), and turn it into a small wave that starts small, gets bigger, and then gets small again. The waves in figure 2, below, are those waves. This is one way to visualize a wave that is representing a quantity of something (a quantized wave as Max Planck envisioned heat energy to be back in 1900).

Figure 2. Qubits as a vessel holding waves that represent a probability of a value, or a probability of an intermediate value

If you take a qubit as a standing wave or a string, you can visualize the wave/string to be vibrating in many directions or dimensions at once. Figure 2, above, shows a possible visualization of a particle as a standing wave. We could imagine that a horizontal wave is spin down, which we consider to mean 0. A vertical wave could be spin up, which we say equals 1. A higher intensity wave means a higher probability of the answer. For example, a full height horizontal wave is a 100% probability of 0. A full width vertical wave is a 100% probability of being 1. Change the tilt of the wave and it becomes a probability of a value between 0 and 1.

When you have a lot of waves with different heights or widths and different angles, in the same qubit, that qubit holds all of those values simultaneously. This is just a metaphor, but a similar thing happens with music. A guitar and a piano can play in the same band at the same time. The piano plays a note at the same time as a guitar and a drum. All of the different notes hit year ear at the same time, so your ear hears several notes from several instruments simultaneously. If an ear can do it, why not a qubit?

Math Problem #1: Very Simple

Time to do some math. Let’s look at a very simple math problem. If the quantum computer is trying to divide two numbers and each can be held with three bits, like 4 divided by 2, the quantum circuit doing the dividing needs to store 4 and 2. It also needs a quantum circuit to perform the division. It also needs a place to hold the answer.

Important Note: Not all qubits in a quantum computer circuit are put in superposition. Qubits can be set to a specific spin state to hold a normal value of 0 or 1. In our simple math problem here, the qubits holding 4 and 2 will not be in superposition. Those qubits are set up to act like regular computer bits. The qubits that are set up to receive the answer from the calculation are in superposition and do hold both 0 and 1 states.

Two in binary is 010, and four is 100. You need three qubits to hold each of those numbers and three more to hold the answer. All three answer qubits start out in superposition as both 0 and 1. When you begin the math to divide 100 by 010, the three answer qubits are ### (if # means 0, 1 and everything in between). When you finish the math and go to read the answer, none of the possible answer qubit value waves (as illustrated in figure 2) are in sync except 010 so everything else falls away. 010 can be seen briefly as spin down, spin up, spin down in the three qubits. The qubit-reading circuits read those values and save them in conventional computer memory.

When a qubit is read to see its final value, the incorrect value waves essentially are out of phase with some sort of a time or dimension-based filter window and they disappear. The wave in sync with the filter window is revealed as the correct answer by the qubit reading system.

When qubits lose their superposition after being read, we call it collapsing. Some people will say “the wave function collapses” and some will say “superposition collapses.”

Fun fact: In 1827, Werner Heisenberg published his uncertainty principle: “there is a limit to the precision with which certain pairs of physical properties, such as position and momentum, can be simultaneously known. In other words, the more accurately one property is measured, the less accurately the other property can be known.” In simple terms, you can know where it is, but not how fast and where it’s going or vice verse.

The implications for quantum computers are that we can let a qubit go about its business of computing, but we can’t know the value while it is computing. We can read its value, but when we do, the qubit collapses and can’t do anymore computation and can’t be read again unless we reset it.

Probability on Today’s Qubits

The quantum computers of today are not yet ready for prime time. They can do a lot, but most still have a lot of refining to go. One of the big problems is that quantum circuits don’t typically give an exact number. Remember items 2 and 3 in the list above: “0, 1 and everything in between“ and “Both 0 and 1 with a probability value of being one or the other“

A simple math problem like 4 / 2 will lead to a high-probability answer - likely 100% probability of being correct on the first try. More complex problems, like factoring large prime numbers give answers with lower probabilities of being correct. Current quantum computers will run the same problem over and over again - often hundreds of times - and combine the results such that the probability of correctness is high enough to be considered correct.

Math Problem #2: A Practical but More Complex Example

Quantum computers breaking cryptographic codes is one of the big fears about quantum computers, so let’s take a look at how that works.

Computer cryptography uses prime numbers to encrypt information and keep it secret. Prime numbers are numbers that have two factors and can only be divided evenly by 1 and themselves. 5 is a prime, because it can only be divided by 1 and 5. Numbers 2, 3, 7, 11, and 13 are also primes. The most common encryption methods in use today use two prime numbers multiplied together as the key. That key is used to encrypt the secret data.

For example: If Jane wants Jim to send her a spreadsheet that is encrypted, Jane’s computer creates an encryption key by multiplying two prime numbers together. In a ridiculously simple encryption scheme, one of the primes is 5 and the other is 7. The encryption app multiplies the two together to get 35 and sends 35 to Jim’s computer as what is called a public key.

Jim’ software uses an algorithm with the number 35 and the spreadsheet to encrypt it. Jim’s email app then sends the spreadsheet back to Jane. Jane’s computer knows that the two factors of 35 are 5 and 7 so it can decrypt the message. No one else knows the original primes (5 and 7), so no one else can decrypt the message. In the real world, very large prime numbers are used for the factors and the key. 35 is easy to break into two primes, but a number with hundreds of digits is not.

Fun fact: 35 is called a public key because anyone can see it. Anyone can use it to encrypt information, but no one can use it to decrypt information. If I get Jim’s spreadsheet and the key, 35, I can’t decrypt the spreadsheet to see what’s inside. The only way I could decrypt it is if I had the private keys, which are the two prime factors: 5 and 7. This is why finding prime number factors of a key is such a big deal. Find the primes and you can read the data.

Sticking with 5, 7, and 35 for simplicity…

To crack the encryption, the cracking software in a conventional computer will take 35 and try to divide it by every prime it knows until it divides evenly.

35 divided by 2 = 17.5 : No. 2 is not a factor of 35.

35 divided by 3 = 11.666 : No. 3 is not a factor of 35.

35 divided by 5 = 7 : Yes. 5 is a factor of 35, as is 7.

That took three division steps to find. But if your prime number factors were 3581 and 7753, and the key 27,753,493, it would take a lot longer. The most common encryption today uses a key with 2048 binary digits (617 decimal digits). With today’s fastest conventional computers, it would take so many computational steps that it is effectively impossible to find the two prime number factors for a number that large

Back to our smaller number. The key, 35, in binary is 100011, the factor 5 is 101, and 7 is 111. Internally, a conventional computer must make the three division calculations with binary numbers:

100011 divided by 000010 (35/2) : No. Not an even number, so not a prime factor.

100011 divided by 000011 (35/3) : No. Not an even number, so not a prime factor.

100011 divided by 000101 (35/5) : Yes. It divides evenly, so it is a prime factor.

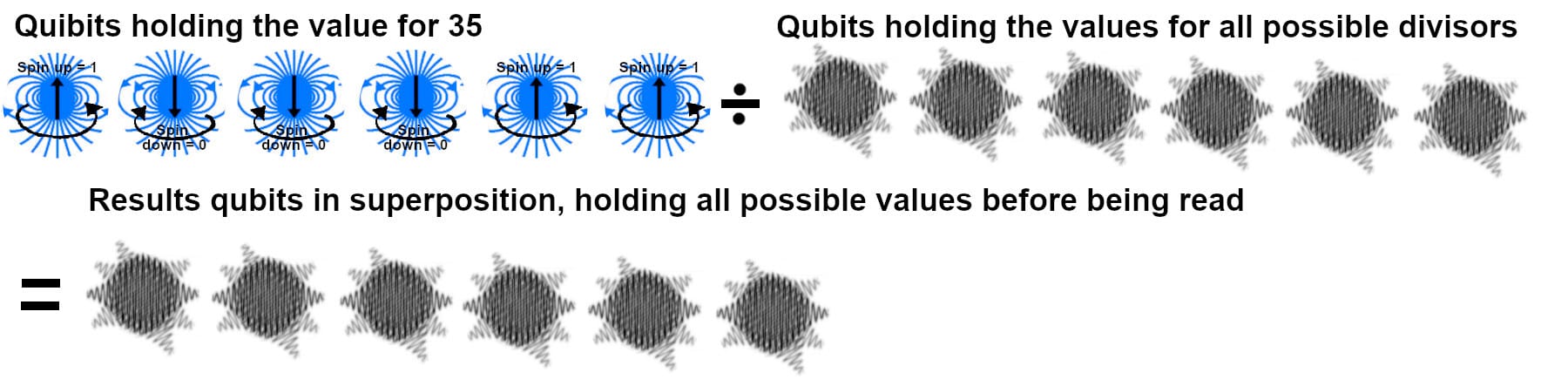

Now let’s do the same set of calculations with a quantum computer. The calculation requires a total of 18 qubits. Six are not in superposition and are set to 100011 (35). Six more are in superposition and hold all possible divisors. for the divisors. The final six qubits will hold the answer. They are also in a state of superposition.

Figure 2. The eighteen qubits being used for this calculation. The first six, holding the binary value for 35 are not in superposition. The six qubits allocated to the divisors are in superposition, as are the six qubits allocated for the answer.

Because each qubit is both 0 and 1 at the same time, the six divisor qubits and the six answer qubits are simultaneously every binary number between 000000 and 111111. It essentially makes all of the division calculations at the same time.

Give the quantum computer the key that you want to factor (100011), tell it to go for one compute cycle, then read the answer qubits. The incorrect wave values vanish, and the only number left is 000101, which equals 5. The conventional computer took three compute cycles to find that 5 is the first prime factor of 35. The quantum computer took one compute cycle. A larger key may take trillions of compute cycles with a conventional computer, but still only take one compute cycle in a quantum computer.

Today’s common encryption would, in theory, take 2048 qubits to hold the encryption key and 2048 more to hold the answer. About another thousand qubits would be required to make up the algorithm logic.

Would That Be Bad?

Yes - if it were only so simple.

In reality, there is no need to panic. As I said in the prior issue, industry experts are developing and implementing alternate forms of cryptography as we speak. Quantum computers can do a lot of things quite well, but they can’t do everything. Some algorithms are, in fact, very difficult for quantum computers to resolve. New encryption, called post quantum cryptography (PQC) uses algorithms that quantum computers can’t decrypt.

A second reason to not panic relates to the current state of quantum computers. They are not yet stable enough to do a lot of work. Superconducting qubits (cooled to near absolute zero) can remain stable for a few milliseconds. That’s long enough for experimental work and for some complex math, but not long enough to crack encryption codes. Further, today’s quantum computers do not contain enough qubits to create the algorithm and store the data. In five to ten years, it will likely be different, but by then, most of our encryption systems will be safe.

In Summary…

Quantum superposition allows a set of qubits to simultaneously perform calculations with all of the possible numbers that can fit in a given qubit space.

Our banking system is still safe (from quantum computers, anyway) because encryption techniques are changing to non-quantum friendly algorithms and quantum computers are still in a primitive state.

How About a More Positive Example?

Breaking encryption and enabling mass theft is not a heartwarming preview of the first great new technology of the 21st century. There are positive examples though.

Certain lines of medical research look at chemical formulas as possible cures for specific diseases. This will often require modeling many thousands of slightly different chemical formulas and their effects on thousands of different types of biological cells. With conventional computers, this is a long and laborious process. A single model might take days, weeks, or months of supercomputer processing time.

In maybe a dozen years, quantum computers will be able to simultaneously perform thousands upon thousands of calculations on these chemicals and cells allowing a lifetime (in today’s conventional compute time) of research to take place in days or weeks (post quantum). That is positive and exciting.

Now, An Easy Way to Review or Catch Up

New to the Quantum Edge newsletter?

Thinking about re-reading it but want a more transportable format?

I’ve wrapped the first ten issues of The Quantum Edge newsletter into book form. The collection, called “The Quantum Computing Anthology, Volume 1”, is now available in Kindle and paperback on Amazon. The book collects issues 1 through 10 and has some additional material and edits for continuity and clarity. I will add another volume to the series every ten newsletter issues, so look for Volume 2 (newsletter issues 11 - 20) in early 2026.

You can order the Kindle and paperback editions on Amazon today: The Quantum Computing Anthology, Volume 1

See You Next Time

Check your email box Thursday - probably. (Okay, some of these weekly issues have come out on Friday, or not at all. But, in a quantum world, how can you tell?)

If you received this newsletter as a forward and wish to subscribe yourself, you can do so at quantumedge.today/subscribe.

Quantum Computing Archive

Below are a few articles on developments in quantum computing:

All About Circuits, Oct 2025: Lattice Brings Post-Quantum Cryptography to Low-Power FPGAs

All About Circuits, Mar 2025: What Does Security Look Like in a Post-Quantum World? ST Looks Ahead

Max Maxfield’s Cool Beans blog, Dec 2024: Did AI Just Prove Our Understanding of “Quantum” is Wrong?

All About Circuits, Dec 2024: IBM Demonstrates First ‘Multi-Processor’ for Quantum Processing

All About Circuits, Aug 2024: Japan’s NTT-Docomo Uses Quantum Computing to Optimize Cell Networks

Independent Resources

Following are some of the quantum computing resources that I regularly visit or have found to be useful:

Microsoft quantum news, Feb 2025: Majorana 1 chip news

Quantum computing at Intel. Read about Intel’s take on quantum computing

IBM Quantum Platform. Information about and access to IBM's quantum computing resources. quantum.ibm.com

Google Quantum AI. Not as practical as the IBM site, but a good resource none the less. quantumai.google.com

IONQ developer resources and documentation. docs.ionq.com

About Positive Edge LLC

Positive Edge is the consulting arm of Duane Benson, Tech journalist, Futurist, Entrepreneur. Positive Edge is your conduit to decades of leading-edge technology development, management and communications expertise.