Quantum computing is one of the first great technologies of the 21st century, but the details are still shrouded in mystery. I can explain conventional digital computing down to the electron in a MOSFET, and with this newsletter, I have made it my mission to do the same for quantum computing.

Welcome to the Quantum Edge newsletter. Here you will read about the physics, chemistry, and all sciences that create the foundation for quantum computing. Join me in my quest to translate the mysteries of the quantum world to the language of the dinner table and the coffee shop.

Issue 19.0, February 5, 2026

In today’s newsletter: Transmons: Qubits Going from Research to Implementation, and how to talk and listen to qubits

Last week I wrote about trapping a single electron and using electrons as qubits. I caveated the choice with: “I mostly think and write in terms of electrons as qubits because they are (or were when I started writing this) the most common particle used as a qubit.“ I missed the boat a bit on that one. Single electron qubits are one of the options and trapped electrons are showing promise in R&D settings. They are not, however, the most commonly used type of qubit.

A better justification for focusing on electrons would be: “I mostly think and write in terms of electrons as qubits because they are a) one of the particles that can be used as a qubit, b) familiar to me because of my electronics background, and c) can be exploited and used as a qubit on an individual scale.” I’ll go with that.

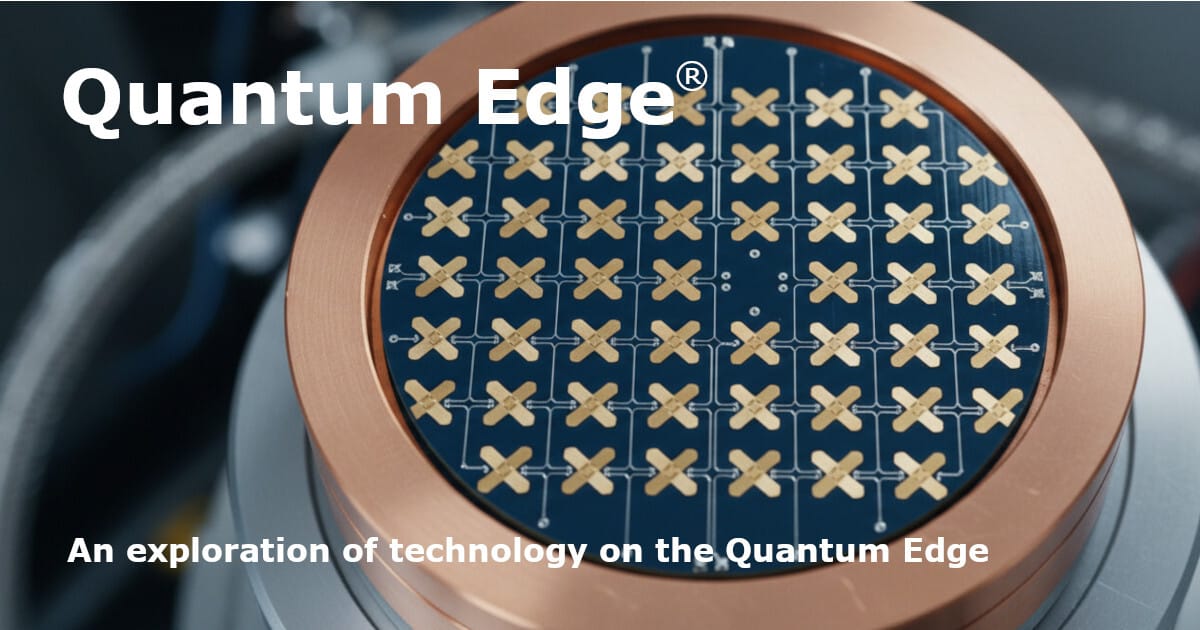

The eventual “most common type of particle used as a qubit” is not settled yet. However, IBM and Google both use devices called transmons as their qubits. Transmons are easier to create and much easier to create in sets on a chip than are trapped electrons. Transmons are often fabricated in a semiconductor together with the microwave network for communications. They do have problems with scaling up the number of qubits on a chip and they aren’t the most stable of qubits, but they work and are currently more stable than a lot of other options, so they deserve a little explanation.

What is a Transmon?

“Transmon” is a shortened version of “transmission line shunted plasma oscillation qubit.“ Goodness. It requires supercooling to get the qubit element down to superconducting temperatures. They operate at just a few tenths to hundredths of a degree K above absolute zero. Contrary to my statement in the prior issue about trapped electron qubits, transmons are the most prevalent type of qubits in large superconducting quantum processors.

Transmons come in the form of a very small circuit (this is going to be another mouthful. Sorry) that combines a non-linear inductor and a capacitor to create a small charge field. They use an architecture called a Josephson Junction, which is constructed of two superconducting materials separated by a very thin insulator with a capacitor in parallel.

The result is a small charge field that can be manipulated with microwaves in the 3–6 GHz range. Each qubit requires a waveguide to direct the microwave energy at it. The charge field operates under the same quantum properties as a single electron qubit.

Qubits are More than Things. They are a Way Things Work

A lot of things can be used to form a qubit. The important message is that “qubit” is more a way a thing acts than it is a thing. When used as a qubit, a transmon is effectively equal to a trapped particle qubit. Today, transmons are easier to build and manipulate at scale, but that may not be the last word in qubits. Something else might come along and work better as a qubit than any of the current structures, or something in use today could be improved enough to win the race. It’s kind of like VHS vs. Beta, but we don’t know which is which yet. (Are you old enough to remember what “VHS” and “Beta” are?)

Microwaves for Qubit Control

Qubits are set up by directing microwave pulses at them. The pulses are set to a frequency that is tuned to the shape of the qubit. Different pulse shapes do different things. Some pulse shapes set up the qubit to hold data. Other pulses set it up to be used as a quantum logic gate. Some pulses set up entanglement or kick off quantum operations.

A qubit state is recovered and read with a microwave resonator that changes frequency depending on the qubit state. The shifted frequency is measured and then sent out of the quantum processor to conventional electronics as a 0 or a 1.

It’s the Same for Most Qubits

Photon qubits do something similar except the pulses are in the light part of the electromagnetic spectrum rather than the microwave spectrum. The operation is nearly identical other than that. Pulses of a specific shape at the right frequency hit the qubit to configure it. Resonators detect energy from the qubit and shift the frequency depending on the state of the qubit and then translate the energy pulses to 0s and 1s based on the frequency.

What is a Qubit?

We’ve asked and answered this question before. However, as we dig deeper, it is worth asking again. More information in our heads means we can take a more complex look at the answer.

A qubit is the smallest piece of a quantum computer that can be used to hold the smallest piece of quantum information. There are a number of ways to create qubits, but as a qubit, every type does the same thing. A qubit holds information in the form of a multi-dimensional vector. When properly manipulated, the 3D vector space collapses into either a 0 or a 1.

A qubit can be a single subatomic particle, but it can also be anything in the quantum world that exhibits the key quantum properties of superposition and entanglement. This includes electrons, photons, some types of individual atoms, some types of grouped atoms, and some fields. As long as it exhibits the correct quantum properties, it can be used as a qubit.

The same principle exists in the conventional digital computing world. The most common type of constructs used as a bit in digital computers is the Mosfet/capacitor circuit and the Mosfet switch. Mechanical relays can also be used, as can old vacuum tubes. Some older computers used resistors and diodes to hold and switch bits. A lot of different things can be used to make and switch a bit - as long as the thing complies with “Benson’s law of useable-for-computing (see newsletter issue 9, or book chapter 10), it can be used as a bit.

Benson’s law of useable-for-computing says that in order for something to be useable for calculation or computing, it must 1) have different states, 2) those states must be stable, 3) the states must be readable, and 4) there must be a way to change the states.

To be a quantum computer qubit, the thing must comply with the same law. Qubits just come with a fifth parameter: “5) operate on the principles of quantum mechanics.”

Stay tuned for more of the quantum adventure next week.

Now, An Easy Way to Review or Catch Up

New to the Quantum Edge newsletter?

Thinking about re-reading it but want a more transportable format?

I’ve wrapped the first ten issues of The Quantum Edge newsletter into book form. The collection, called “The Quantum Computing Anthology, Volume 1”, is now available in Kindle and paperback on Amazon. The book collects newsletter issues 1 through 10 and has some additional material and edits for continuity and clarity. I will add another volume to the series every ten newsletter issues, so look for Volume 2 (newsletter issues 11 - 20) in early 2026.

You can order the Kindle or paperback editions on Amazon today: The Quantum Computing Anthology, Volume 1

See You Next Time

Check your email box Thursday - probably. (Okay, some of these weekly issues have come out on Friday, or not at all. But, in a quantum world, how can you tell?)

If you received this newsletter as a forward and wish to subscribe yourself, you can do so at quantumedge.today/subscribe.

Quantum Computing Archive

Below are a few articles on developments in quantum computing:

All About Circuits, Oct 2025: Lattice Brings Post-Quantum Cryptography to Low-Power FPGAs

All About Circuits, Mar 2025: What Does Security Look Like in a Post-Quantum World? ST Looks Ahead

Max Maxfield’s Cool Beans blog, Dec 2024: Did AI Just Prove Our Understanding of “Quantum” is Wrong?

All About Circuits, Dec 2024: IBM Demonstrates First ‘Multi-Processor’ for Quantum Processing

All About Circuits, Aug 2024: Japan’s NTT-Docomo Uses Quantum Computing to Optimize Cell Networks

Independent Resources

Following are some of the quantum computing resources that I regularly visit or have found to be useful:

Microsoft quantum news, Feb 2025: Majorana 1 chip news

Quantum computing at Intel. Read about Intel’s take on quantum computing

IBM Quantum Platform. Information about and access to IBM's quantum computing resources. quantum.ibm.com

Google Quantum AI. Not as practical as the IBM site, but a good resource none the less. quantumai.google.com

IONQ developer resources and documentation. docs.ionq.com

About Positive Edge LLC

Positive Edge is the consulting arm of Duane Benson, Tech journalist, Futurist, Entrepreneur. Positive Edge is your conduit to decades of leading-edge technology development, management and communications expertise.