Quantum computing is one of the first great technologies of the 21st century, but the details are still shrouded in mystery. I can explain conventional digital computing down to the electron in a MOSFET, and with this newsletter, I have made it my mission to do the same for quantum computing.

Welcome to the Quantum Edge newsletter. Here you will read about the physics, chemistry, and all sciences that create the foundation for quantum computing. Join me in my quest to translate the mysteries of the quantum world to the language of the dinner table and the coffee shop.

Issue 18.0, January 22, 2026

In today’s newsletter: Trapping an Electron - Doing the Seeming Impossible

Getting Back to Qubits

Electrons, photons, complete atoms, and groups of atoms are some of the items that can be used as qubits. I mostly think and write in terms of electrons as qubits because they are (a one of the particles that can be used as a qubit, b) familiar to me because of my electronics background, and c) can be exploited and used as a qubit on an individual scale.

Electrons rely on their spin property. Atoms and groups of atoms rely on collective spin. Photons rely on polarity as their changeable property. Many things can be a qubit, but, as I said before*, they all need a quantum property that has more than one state which can be switched and read. All the above fit that bill.

In issue 9, I state: Benson’s law of useable-for-computing says that in order for something to be useable for calculation or computing, it must 1) have different states, 2) those states must be stable, 3) the states must be readable, and 4) there must be a way to change the states.

It’s fine to explain that a quantum computer uses a subatomic particle as a qubit, but when you really think about it, you might end up asking how a single particle can be harnessed, held, and manipulated. Normally that is something that is just not done. Subatomic and atomic particles are too small.

But it is done, so that begs the question: how? The answer takes a bit of a circuitous route to get to. I have to start with a copper wire.

Most wires are made of copper because copper has a high electrical conductivity and is affordable. High conductivity comes from the electrons in the outer band, which can also be described as the electrons at the highest energy level*. Copper (Cu) is element 29, meaning it has 29 protons and (in non-ion form) 29 electrons. That’s a fair number of electrons, but not all of them are useful for conducting electricity - only one is.

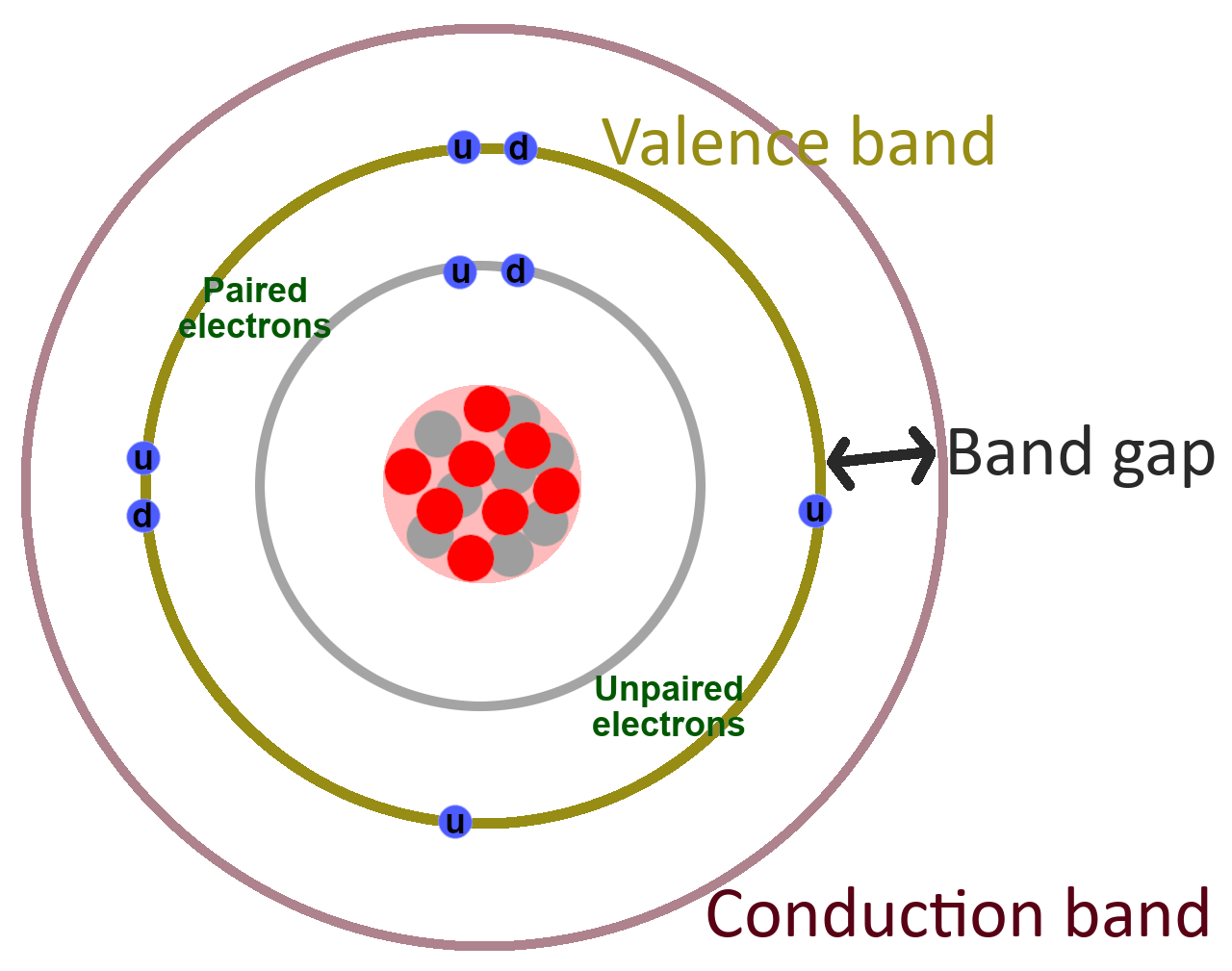

* Long-time-ago physics described electrons as being small particles orbiting at specific distances from the nucleus. This way of picturing atoms is called the Bohr model after its creator, Niels Bohr.

The model shows the protons and neutrons tightly packed in the nucleus in the center, and electrons spaced out in specific orbital bands. In today’s physics, these orbits are typically described as the energy levels of the electrons. For our purposes (at least in this issue) the difference between calling it an orbital band or an energy level doesn’t really matter. It’s a bit easier to think of orbits, so I’ll use more of that lingo here.

Copper is a conductor, but atoms that insulate (don’t normally conduct electricity) are equally important. We must take a look at a non-conducting atom to fully understand how electrons move around. Oxygen is a non-conducting atom and is quite common, so I’ll start there.

Figure 1. Bohr model of an oxygen atom with a large band gap between the valence band and the conduction band

Figure 1 shows the Bohr model of an oxygen atom. It has eight electrons total. Two in the inner orbital band and six in the outer, or valence, band. In most atoms, the highest orbit is called the valence band. This is typically the highest orbit (or energy level) for electrons to naturally occupy in an atom.

There is another band, called the conduction band, that is at or past the valance band. Electrons must be in the conduction band in order for the material to conduct electricity, but in many atoms, the conduction band is farther away from the nucleus than the valance band, so it doesn’t naturally have any electrons.

No electrons exist naturally in oxygen’s conduction band, so oxygen is an insulator. If the atom were hit with enough energy, like the energy in a lightning bolt, an electron might be energized enough to jump across the band gap into the conduction band, causing the atom to become a reluctant conductor.

That’s how a spark happens (lightning is a giant spark). The atoms and molecules that make up air are insulators (no electrons in the conduction orbital band). A high enough voltage energizes an electron, causing it to jump to the conduction band. Do this to enough atoms and you get a spark through what would otherwise be an insulator.

Conductors and Insulators

The conduction band is a region where the electrons are far enough from the nucleus that they are not locked into place and can be coerced into moving. The distance between the valance band and the conduction band is called a band gap, and the band gap differs with different atoms.

Atoms like oxygen (shown in figure 1), chlorine, helium, and materials, like glass and plastic that don’t conduct electricity don’t have any electrons in their conduction band. In order for a material to conduct electricity, the top-level (valance) electrons must jump the band gap between the valance band and the conduction band. Atoms with a large gap between the valance and conduction bands are difficult or impossible to be used as a conductor. We call these atoms (and the materials made out of them high band gap materials. They make good insulators.

Figure 2. Copper atom showing single electron in valance band, which happens to be in the conduction band

Metals have a very small band gap. In fact, in many metals the conduction band and valance band overlap. Copper (figure 2) has a single electron in its outermost (valance band) and its valance band overlaps with its conduction band. It effectively doesn’t have a band gap and that electron is just waiting for an opportunity to jump to another atom. This movement of an electron from one atom to another is what we call electric current. That solo electron in the top band is the only one of the 29 total electrons in a copper atom involved in electric current flow.

Back to the Copper Wire. Current, Electric Potential, and Power

Going back to the copper wire…

The wire going from your car’s 12-volt battery to the car’s starter motor is really thick copper. When you start your car, a lot of electrons rush from the battery to the starter motor. The number of electrons moving at the same time is called the current (measured in Amps). Your car starter motor performs a lot of work starting up your cold engine on a cold morning, so it needs a very high level of current. High current requires a large wire so the electrons don’t squeeze into each other (bump into each other) too much.

In the last issue, we learned that heat is particles bumping into each other. If you have too many electrons trying to move through too small a wire, they will bump into each a lot and heat up. Enough of this bumping and you will start a fire.

The speed at which the electrons want to jump from atom to atom is what we call electric charge potential (measured in Volts). Some people describe it as pressure behind the electron, but I think for our purposes, either the pressure behind it or the speed the electron wants to go works equally well.

Your car battery has a 12-Volt electric potential and can supply maybe 300 Amps of current.

Current is measured in Amps

Electric charge is measured in Volts

Power is measured in Watts

Power

When you multiply Volts and Amps together, you get the total power from the electricity. Power is measured in Watts. 12 Volts at 300 Amps can produce 3600 Watts of power. You might then guess that 300 Volts at 12 Amps could also produce 3600 Watts of power.

You would be correct.

Volts times Amps = Watts

Amps times Volts = Watts

So, what’s the difference between 12 Volts at 300 Amps and 300 Volts at 12 Amps? They both produce the same amount of power. Right?

Yes. They do both produce the same amount of power. But a few things are different. Higher current (high Amps) needs more copper because more electrons are flowing at the same time. High voltage can use a thinner wire, but the electrons are moving faster so they might be able push through the band gap of the surrounding insulating material and conduct to a place they should not go. Higher voltage needs more insulation to keep it in its place.

Voltage is potential electric charge which can be described as the speed the electrons want to go. A faster electron can jump farther (just like a faster human can jump farther). Higher voltages may have enough energy to move the electrons in the insulator across the band gap from the valance band to the conductive band. High enough voltage can do the same thing with air, which is what happens when we see a spark.

High current = more electrons moving at the same time so you need more copper

High voltage = electrons are moving faster so you need more insulation

Now, Trapping One of those Electrons to Make a Qubit

We need to catch and hold one of those electrons in order to create a qubit. One of the ways to trap and hold a single electron is called a Penning trap. In a Penning trap, a single electron is caught by what is called a quadrupole magnet. Electrons, as J. J. Thomas discovered in the 1890s, can be controlled with magnetic fields.

Figure 3. A Penning trap holding a captured electron

The Penning trap starts with a very small wire. So small, in fact, that only a single electron can move through it at a time (that’s a super small current). The wire leads to a small gap that has four electromagnets (the quadrupole magnet) surrounding it. There is an outgoing wire on the other side of the gap. The electrons are moving fast enough (at high enough voltage) such that they can jump across the space between the incoming wire and the outgoing wire while the quadrupole electromagnet is turned off.

When an electron is in that gap, the quadrupole is energized and the electron is trapped. With the election trapped, the next electron can’t jump across the gap. No more current flows and that electron stays in place as long as the four magnetic fields are balanced. The trapped electron can now be used as a qubit.

A Penning trap can hold onto its electron for quite a while. That makes it suitable for use in creating and using qubits. There are other ways to trap particles, but the end result is the same. You have an electron (or other particle) held in place so you can do things with it.

Now that we have a trapped electron, we can uncover the ways quantum computers turn particles into qubits and manipulate them, but that’s it for today. Stay tuned.

Now, An Easy Way to Review or Catch Up with the Quantum Edge Newsletter

New to the Quantum Edge newsletter?

Thinking about re-reading it but want a more transportable format?

I’ve wrapped the first ten issues of The Quantum Edge newsletter into book form. The collection, called “The Quantum Computing Anthology, Volume 1”, is now available in Kindle and paperback on Amazon. The book collects newsletter issues 1 through 10 and has some additional material and edits for continuity and clarity. I will add another volume to the series every ten newsletter issues, so look for Volume 2 (newsletter issues 11 - 20) in early 2026.

You can order the Kindle or paperback editions on Amazon today: The Quantum Computing Anthology, Volume 1

See You Next Time

Check your email box Thursday - probably. (Okay, some of these weekly issues have come out on Friday, or not at all. But, in a quantum world, how can you tell?)

If you received this newsletter as a forward and wish to subscribe yourself, you can do so at quantumedge.today/subscribe.

Quantum Computing Archive

Below are a few articles on developments in quantum computing:

All About Circuits, Oct 2025: Lattice Brings Post-Quantum Cryptography to Low-Power FPGAs

All About Circuits, Mar 2025: What Does Security Look Like in a Post-Quantum World? ST Looks Ahead

Max Maxfield’s Cool Beans blog, Dec 2024: Did AI Just Prove Our Understanding of “Quantum” is Wrong?

All About Circuits, Dec 2024: IBM Demonstrates First ‘Multi-Processor’ for Quantum Processing

All About Circuits, Aug 2024: Japan’s NTT-Docomo Uses Quantum Computing to Optimize Cell Networks

Independent Resources

Following are some of the quantum computing resources that I regularly visit or have found to be useful:

Microsoft quantum news, Feb 2025: Majorana 1 chip news

Quantum computing at Intel. Read about Intel’s take on quantum computing

IBM Quantum Platform. Information about and access to IBM's quantum computing resources. quantum.ibm.com

Google Quantum AI. Not as practical as the IBM site, but a good resource none the less. quantumai.google.com

IONQ developer resources and documentation. docs.ionq.com

About Positive Edge LLC

Positive Edge is the consulting arm of Duane Benson, Tech journalist, Futurist, Entrepreneur. Positive Edge is your conduit to decades of leading-edge technology development, management and communications expertise.